By Adesuwa Agbonile

Claire Foley’s housewarming party was an obligation, so Temidayo Soyinka went. Went, even though he was not feeling like himself. Went, even though over the past few days, his body – elegant object, finely-tuned thing – had begun to fail him.

Temidayo had struggled through colds and flus, but this was unlike any sickness he had ever encountered. Some strange, unnamable poison was circulating through his blood, gnarling his insides and discombobulating his outsides. Movements that were once second nature to Temidayo had turned exhausting. Swiping a metrocard, pushing through the turnstile, descending the stairs, settling into a seat on the train – each gesture, a challenge to puzzle through.

But Temidayo was a Soyinka, and Soyinkas never shirked an obligation. They were always doing the things that had to be done. Which is why Temidayo was able to force his body off the train at the right stop, and force his legs to make the walk to Claire’s new apartment. She had moved into a sleek building in the East Village, one of those places where everything was shiny with renovated newness but also seemed put up in too much of a rush, and so radiated a strange hollowness, like if you poked too hard at one of the supporting beams it would pop and the ceilings would fall on top of you. It suited her, though; Temidayo sat on Claire’s new couch and watched her from across the room, glittering in a new cocktail dress, laughing at every one of Mark’s jokes, and she, too, seemed shiny and new and strangely hollow.

T. Hey, what’s up.

Temidayo watched Jack fill the empty space on the couch next to him. He had known Jack since freshman year, and had hated him for almost as long. But Jack had gone to some boarding school in the east, the type that had presidents as alumni. Temidayo had recognized the boy’s social capital – Jack was the one who had introduced him to half of the people at this housewarming, including Claire – and his body had adapted, his mouth had learned how to talk to the boy. When Jack leaned forward contritely, Temidayo could see the skin flaking off around his nose ring. He wanted to give the boy a bottle of vaseline and a warning.

I feel like I haven’t seen you in years, Jack said.

Temidayo settled into the couch, and waited for his mouth to begin speaking for him. His mouth – lovely instrument. Shaped just right. Temidayo never had to think about what to say; his mouth did the work for him. Every word uttered emerging shimmering, lighter than air, floating through space before dissolving with a pleasing fizz against the ear.

At least, this is how it used to be. Now, Temidayo was surprised to discover that his mouth refused to speak. He did not utter a word.

If Jack noticed – which Temidayo doubted he did – he was polite enough to fill the silence.

You know, she told me how much she pays in rent earlier, he said. It made me want to throw up. Jack laughed at this; Temidayo forced out a chuckle. He felt nauseous. His whole body had begun to burn. He pulled up his sleeve to examine his forearm. His skin looked fine, but felt hard and scabbed over, like if he dragged a fingernail up his arm, it would pull away like bark.

She is such a bitch, by the way, Jack said. I know you can’t say that. At least, not yet. I’m saying it for you.

This was the kind of backhanded compliment Temidayo’s mouth usually excelled at responding to. But still – nothing. His mouth had abandoned him. Against his will, without his consent, his entire body had curdled, turned in on itself.

Enough about me, Jack said. Tell me about you. Claire said she saw you at the beach this weekend. All alone! You should have invited some of us. I would have come.

Temidayo finally forced his mouth open by himself. It was like tearing open a healing wound.

Um. he said. I didn’t – I wasn’t alone.

Claire said you were all by yourself.

No, I – no. I was. I was with a girl.

Just mentioning her conjured the scent of citrus. The sound of the tide. That flat feeling after a theft.

Jack was aglow with interest, his nose ring humming with voltage. What girl? He said. Who’s the girl? And Temidayo could practically see her there, standing beside Jack, smiling that perfect smile, eyes glinting, raising her eyebrows as if to say, yes, speak, go on. Tell, while you still can.

Well, Temidayo said. I met her at the beach.

This was not entirely true. Their first real conversation was at the beach. But Temidayo had noticed the girl almost a year earlier, right after she moved into his building.

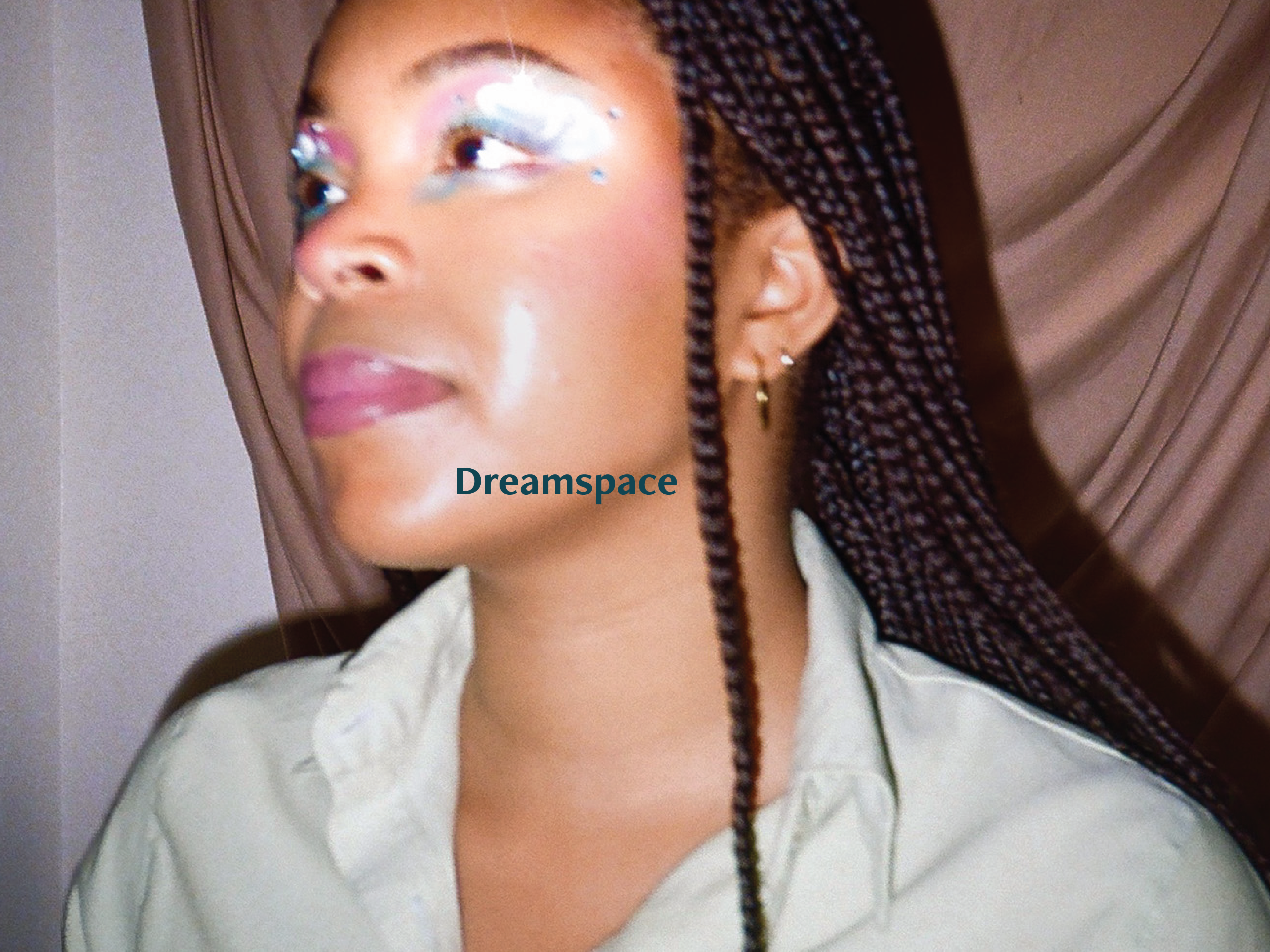

It was impossible not to notice her arrival – one day, she was not around, and the next, she Was. A change so sudden and abrupt it was divine; God commanding light. Temidayo witnessed genesis in front of the mailboxes. There she was, tapping rhinestone-tipped nails against metal, working her key into the slot. He stood beside her to collect his mail and she smelled like oranges and wet earth. Shea butter skin. Richly adorned – jewels hanging from her ears, flashes of gold on her fingers.

It was the end of April when the girl came, and she pulled spring along behind her. New life sprouting up in her shadow. The air turned warm and sweet. The Saturday after she moved in, Temidayo came downstairs to collect a package, and there she was, orange grove beauty, breezing past with a picnic blanket under her arm. She was dripping in white and soft pink, cowrie laced into her twists and hanging from her ears and clinging to her waist. Foamy mouth of ocean. Temidayo watched her leave, and turn right – walking in the direction of Prospect Park. Her body, a receding tide.

Thirty minutes later, Temidayo had decided that he, too, had better spend the day in the park. Walking his body in the direction of the trees felt strange – Temidayo was used to turning left, walking the two blocks to the train. Barrelling into Manhattan. He liked Brooklyn – he found strange comfort in knowing that when he was sleeping, everyone he called friend was a river away – but he usually spent his days in the city, with Claire and Jack and their assorted friends. But this spring Saturday, Temidayo decided instead to follow the girl into the park, pulled along by a ringing certainty that was not of his body, but outside of it, like metal pulled towards a lodestone.

Temidayo was sure he wouldn’t find the girl until he did. There she was, sitting by the water, right where the grass lawn gave way to a thick grove of trees. She lay between two humongous oaks with headphones on, bobbing her head to an invisible rhythm, looking up at the sky. The tree’s branches rose and curved downwards, creating a canopy just for her.

Temidayo found himself breathing manually. He laid out his blanket a respectable distance from her. He pretended he wasn’t watching her. He watched her.

He watched her light a joint. He watched her turn to face the tree trunk closest to her, and splay her hand out against the bark. He watched her lips begin to move, and then he watched her throw her head back and laugh.

She was talking to the tree. She leaned in closer to the trunk, and widened her eyes, like she was learning a secret. She was talking to the tree, and – the tree was talking back.

Suddenly, she frowned, turned her head, and looked directly at Temidayo, who did not have time to look away. They stared at each other. Temidayo felt something inside of him crack open. The girl smiled, and raised her hand.

Temidayo’s body refused to move of its own accord. All he could think to do was mirror her movement - raising his left hand, waving it. Her smile grew.

They continued this wordless routine through the spring. Summer came; and the long and languid days let Temidayo follow his whims without any sort of guilt. In these golden months, Temidayo spent hours in the park. He memorized the girl’s body. The curve of it. The undulation of her hips as she walked. The slight bend of her spine when she laid flat on her blanket. She was a glowing red core draped in dark brown. Temidayo’s personal sundial.

Temidayo kept waiting for his body to take over. Eventually, surely, his legs would walk him over to her and a coy and charming line would float out of his mouth. But all he could ever manage to do was sit at a distance, and gape at the girl.

Temidayo never told anyone about the girl. His mouth wouldn’t allow it. It was for the best – if he had tried, he would not have been able to articulate what drew him to her. He would not have been able to describe the feeling that overwhelmed him as he sat and watched the girl write in her journal, talk to trees, lay back and smoke – a feeling of kinship, of sameness split down the middle. When Temidayo watched the girl, it was like looking into a trick mirror and discovering in the warped reflection the face he knew he had all along. But all of this feeling was happening in a place inaccessible to Temidayo, in a hollow space boxed in by the impenetrable fortress of his body.

Fall arrived, and Temidayo watched the girl hold her hand out to catch the orange brown falling from the branches of the trees above her. The motion felt like an ending. It would soon be too cold to lounge in the park, and still, his body refused to move towards the girl, speak to her. Temidayo and the girl continued to trade glances of recognition, the occasional wave.

And then, one December morning, Temidayo went to the park and saw that some parts of the lake had frozen. He waited for the girl. She never came. Eventually, his body picked itself up, and took him back home.

In the winter months, Temidayo didn’t dwell on her. He was confident that his body knew best. If his body had not moved to speak with her, then she was not for him. It was that simple.

Temidayo had crafted his body himself, over many years, shaping it just right so it would motor him through the world alive, powerful, free. This ability was a family trait, a Soyinka magic passed down from generation to generation, just like Temidayo’s broad nose, the purple layer under his dark skin.

Temidayo’s mother was the one who had taught him this family skill – an irony, because the woman had married into the family. But she had chosen her husband in part because he felt so familiar to her, and when she took on the Soyinka name, she slipped into the family’s magic. It had always been a part of her, and she a part of it.

She gave Temidayo his first lesson at four years old. I have to go to work, she said, so you have to make yourself breakfast. Temidayo protested – he did not know how. His mother leaned down, took his shoulder, and said, very gravely: Temidayo, you are a Soyinka. If you tell yourself something must be done, there is no way it will not get done.

So Temidayo told himself, I have to make breakfast. And then a strange thing happened - he felt his body swirl and pulse, then watched as his hands went to collect microwave oatmeal from the pantry, watched as they tore open the packets, added milk. He watched his legs bend and jump so he could climb the counter and reach the microwave. Temidayo told himself that he had to make breakfast, and then he did. This was when he began to understand that he could make himself into a person who could do anything he pleased. He could build a body that arced him through the world like a sharp sword.

It was a strange sleight of hand - a magic trick, really, this ability to rubber one’s body, to melt oneself down and fashion oneself into any tool to do any task. Temidayo could bend, stretch, twist his body into any shape. And at 24, freshly graduated, ensconced in a plush venture capital career, Temidayo had just about finished construction on what he considered to be the perfect body. Mouth shaped to feign honesty but guard secrets carefully. Shoulders broad enough to convey solidity. Hands soft, demonstrating openness. Fingers long, nimble enough to manipulate. Legs toned to kick continuously, to keep Temidayo afloat in his world of cocktail mixers and client meetings and expensive bottle service and housewarming parties, endless housewarming parties, revolving doors of performance and wealth, and there, on every couch, was Temidayo, star player, suave interloper, sweet friend, ferocious businessman, Soyinka child. His body ruthless in pursuit of its inputted mission – doing, always, what had to be done.

It was this body that had moved Temidayo in Claire’s direction in the wintertime. The two of them had been circling each other since freshman year, but this winter in the city felt particularly lonely. One night Temidayo found himself himself on Claire’s couch in her old East Village studio, eating dinner next to her, and he felt his head turn toward her, felt his mouth open, and heard himself say, can I kiss you, and she smiled and said, sure, and they came together, and Temidayo could taste his own words on her lips. They were saccharine. Their bodies fit together just right, like a key sliding into a lock.

It was an easy winter. Temidayo liked the simplicity of Claire. One of them would text, or call, and the other would come. They laid up late and traded secrets. She told him about the time she was seized by a panic attack while biking home from class, and dragged her bike to the side of the road so she could curl up under it and weep for a full hour. He told her about the summer he had become obsessed with mastering the game of lacrosse after playing a friendly round with some consulting interns and getting thrashed. She told him about her tendency to get up in the middle of the night and stuff her face full of brownie bites.

Claire told almost none of their friends that they were sleeping together. She liked to flirt with other men in front of Temidayo, but burst into tears the one time he mentioned the prospect of sleeping with other people. This wasn’t particularly bothersome in the winter, but as the cold peeled away, Temidayo’s mind began to wander. He knew that the girl checked her mailbox every day around eight, and he started loitering by the boxes around then just for the opportunity to catch a glimpse of her. Swishing skirts and cropped t-shirts. Temidayo found that sometimes when he slept with Claire, his mind would replace her body with the girl’s. He would turn Claire over onto her stomach and catch a glint of the girl’s cowrie waistbeads. Kiss Claire and taste orange. He assumed Claire didn’t notice, until one morning they were lying in bed together and she looked up at the ceiling and said, sometimes it feels like you’re looking straight through me, and Temidayo said, well, I’m not, and Claire said, yeah obviously. It just feels like that.

Temidayo had no response to this, which was just as well – two weeks later, Claire started sleeping with Mark Moore, who Temidayo knew vaguely from college and who worked at the same firm as Claire. She told Temidayo about Mark with a straight face, and asked politely that he to take home the sweatshirt he sometimes left at her apartment.

Their separation marked the beginning of summer, and with the heat came memories of the park. The first Saturday after Claire ended things was an unusually hot day. Temidayo woke up early and hung around the mailboxes until the girl came downstairs. She had on a neon pink bikini top. Same waist of cowrie. A sun hat. When she left the building, she went left - towards the train.

He knew, without having to ask, where the girl was going. He went back up to his apartment, put on some swim trunks, packed some food, and followed her to the beach.

Temidayo walked along the sand and scanned the rows of people, looking for the deity in their midst. After half an hour, he wondered if he had chosen the wrong beach. Or maybe she hadn’t gone to the beach at all? But then he spotted, near the water, pink and cowrie. The lip of the sky meeting the foamy mouth of the ocean. There she was.

It was like witnessing a miracle. Temidayo stopped in his tracks and gaped. The girl felt his gaze, and turned to look. Recognition bloomed across her face. They went through the usual motions: she smiled, and held her hand up in a wave. Temidayo smiled, and waved back.

And then, a curious and wretched thing - his body began to turn away from the girl, moving him further down the beach.

In the last weeks of spring, Temidayo had convinced himself that Claire was the thing standing between him and this girl from his building. He had forgotten the real problem, the original problem: his body. It was his own body, the one he had built by hand, that refused to talk to this girl. It was his body that had decided that this girl would not fit together with Temidayo, the way Claire had. It was his body that had kept whatever strange feelings Temidayo had towards the girl contained, prevented them from leaking out.

But – it was summer. Temidayo let himself follow his whims. And so, against his body’s better instincts, he turned himself around, returned to the girl, and widened his mouth into what he hoped was a smile.

Hey, neighbor. Funny seeing you here.

The girl laughed. There was a tug in the bottom of Temidayo’s stomach. What’s funny? he said.

Oh, nothing. You just sound different, than how I imagined.

Her voice was deep, singsong-y. Every syllable teetering on the edge of music.

I guess I should have talked to you sooner.

The girl raised her eyebrows at this, but said nothing.

Um, Temidayo said. Um. I’m surprised you came here instead of the park.

Why’s that?

Ah. Well. You can’t pretend to talk to trees here.

The girl laughed again. Who said I was pretending?

Temidayo played along. Then what do they say to you?

Actually, they have a lot to say about you.

It was Temidayo’s turn to laugh - a yelping sound that startled him when it emerged. It was not a laugh he had shaped or built. He was not sure where it had come from. But when the girl heard it, she smiled up at him. Temidayo watched interest settle in behind her eyes.

Do you want to sit down? she said.

Temidayo grinned, and laid down his beach blanket next to hers. She pointed to the cooler bag slung across Temidayo’s shoulder.

I know there’s food in there.

A soothsayer.

Yeah, Temidayo said. Yeah, there is.

They laid in the sand, eating the Ritz crackers and cheese that Temidayo had brought along. He thought he had only packed enough food for himself, but the girl found a way to make everything stretch and double. He was trying to find a way to ask her how she was doing this (awful challenge – he hadn’t had to think this much about what he was trying to say since middle school), but the girl answered the question before he had finished trying to articulate it.

I had to teach myself how to get used to abundance, she said, making a little cheese sandwich for herself with Ritz crackers. And then, when I got used to it, I found that it was all around me.

Temidayo mimicked the girl and made a sandwich with his crackers. I'd like for you to teach me that.

The girl laughed. Or you could teach yourself. I had to learn how to move through this world on my own.

Me too, Temidayo said. His hand instinctively reached up to his mouth. Upon seeing the motion, the girl brought out a joint, and waved it in front of Temidayo’s face.

Do you smoke?

Oh, absolutely.

The weed made everything hyperreal. Temidayo looked out past the people on the beach to the water and watched the waves, silent beams of energy pushing through water and then crescendoing into white and sound, rushing towards the shore.

The girl asked him about his thoughts on their super, and Temidayo was grateful for the question, an easy opportunity to establish points of commonality. They gossiped about the man’s tendency to ignore maintenance requests, then moved on to other things – a heated debate about the best food in their neighborhood, several percolating theories of the identity of the building's resident package thief.

The words that they passed back and forth felt solid in a way that Temidayo was unused to. The girl’s sentences curled around his ribcage and burrowed past his body, into the hollow space at his center. As he lay on his blanket he felt weighed down by her, in a pleasing way, like when he was little and would go to the beach with his mother, and the woman would bury him in sand, both of them laughing until only Temidayo’s face was visible above the earth. Talking to the girl felt like being buried in earth, being planted in preparation for spring.

Eventually, their conversation moved to the park, and the previous summer. You know, the girl said, I kept waiting for you to talk to me. And wondering why you never did.

Honestly, I think I was waiting for me to talk to you, too.

The girl turned to him then, and Temidayo glimpsed a shadow pass across her face. He wondered if he had said something wrong.

Yeah, she said. I guess that makes sense.

But I mean - I talked to you today.

You did. So what changed?

Before Temidayo could respond, a fluty voice arced through the air.

T! The voice called out T! T!

The girl grinned. Who calls you T? she said, and then looked over Temidayo’s shoulder and waved jovially at the figure there. Temidayo turned to look, even though he only knew one voice shrill enough to pierce the air like that. It was Claire.

Claire’s honeydew bikini gave her skin a dim, chalky color; she was all pastel. Standing next to her was Mark, the new boyfriend. Sturdy and solid. Temidayo looked at him, and felt his spine lengthen and straighten. His mouth tilted up. Gestures all meant to convey one message: you are no threat to me. This was a situation his body was well-prepared for.

T, T! I knew that was you.

It was lost on Claire that she should be embarrassed. That while she was out with Mark, her new boyfriend, she should avoid Temidayo, the last one. She was treating him like shit. She was treating him like shit, on purpose. And she thought that she was going to get away with it.

Temidayo suddenly wished he had invited someone that Claire knew to the beach with him – Trisha, or Payton; anyone who would make Claire sit up straight. He wanted to make jealousy fester and congeal under her skin in streaky, pastel pink.

You know Mark, right? Claire said.

Yeah – Econ one-oh-one. I still barely know what a demand curve is.

Claire and Mark both laughed at this, a reassuring sound. A sign he was moving in the right direction.

I didn't realize you were in the city until Claire told me, Mark said.

Claire likes keeping me a secret, Temidayo said. He watched Claire grow pink, and he felt his body gaining control, gathering up its power to push him to the end of this conversation. He turned to Mark with a wry smile, and lowered his voice.

Has she told you about how sometimes she gets up in the middle of the night to eat brownie bites?

Claire deflated. Mark laughed again. I was wondering why there were crumbs in my bed the other night.

Temidayo smiled, and turned to Claire. Don’t worry, though, he said. It’s cute. Under her skin – a collection of pastel pink.

You guys are stupid, Claire said. Her earlier cheer was gone.

You sound like our Econ professor, Temidayo said. Another laugh from Mark. Claire’s mouth was set in a straight line.

We have to go, she said. But, T - you’re coming to my housewarming next weekend, right?

Temidayo had been planning to skip it. But now that Claire was specifically inviting him, it would mean something if he didn’t go.

I’ll be there, he said.

An obligation. His body stored the information away, fuel for whatever it needed to do next. Mark reached down and tapped Temidayo’s shoulder.

We gotta get drinks sometime. He said it so quickly and insincerely there were no gaps between his words. Wegottagetdrinkssometime.

Temidayo felt his mouth expand into a smile, despite the fact that he was imagining strangling Mark to death. It was what he had trained his body to do - it was why he loved the ornate machine.

We’ll leave you alone now, Claire said. We have to find a spot to sit.

The fact that she was leaving - and not rolling out her towel to lay beside Temidayo and bask in her new-boyfriend glow - was confirmation of Temidayo’s victory.

It was good to see you, he said.

Housewarming. Don’t forget.

I wouldn’t dare.

Claire and Mark marched down the beach, further and further away. Temidayo watched them until they faded into every other body on the strip of beach, until every woman picking her way across the sand became a gesture of Claire.

Temidayo’s high, jolted out of his system by Claire’s sudden appearance, eventually returned, relaxing his muscles, sharpening his ear. The sound of the waves returned to his focus. He looked out at the ocean and heard the swoosh of the water against the shore. The more he listened, the more he heard something like chattering. Streams of language moving in rhythm with the pushes of water. Hello there. Listen carefully. Who’s this? Shall we welcome him in? Goodbye.

Well, okay, bye. And this voice was much closer, more immediate. Temidayo turned to look beside him, and was surprised to see the girl standing above him, folding up her towel.

Oh! He said. And then, because his mouth still refused to speak on his behalf when it came to this girl, he scrambled to put together a sentence. Wait, he said. Wait – I don’t want you to leave. It was the realest, plainest thing he had ever said.

The girl frowned. That’s a weird thing to say, she said. Two seconds ago, I was invisible to you.

What? What do you mean?

The girl finished folding her towel, turned on her heel, and started walking in the direction of the train. Temidayo had to jump up and jog to catch her.

Hey! I asked what you meant.

I meant what I said. You couldn’t see me. And neither could that girl or her boyfriend.

Oh, come on. Temidayo was surprised the girl was fishing for a compliment. Of course I can see you. You’re beautiful.

The girl’s laugh was loud, and mean.

You’re not listening. I said I was invisible.

Well. Obviously I can see you. And so could Claire and Mark.

They didn’t say a word to me.

That’s just - how they are.

The girl stopped in her tracks abruptly, and swiveled to stare at Temidayo. She was incredulous.

You don’t believe me.

Just like with the trees, Temidayo couldn’t tell if the girl was joking or not. I mean, he said. People can’t literally be invisible. Claire and Mark were just ignoring you, honestly.

I asked you to introduce me.

What?

I tapped you on the shoulder and said - introduce me! But you couldn’t hear me. Or see me. Because I was fucking invisible.

As she talked, the girl tapped her index finger against her temple – universal symbol for get this through your thick skull.

You didn’t say anything, Temidayo said. He was beginning to think the girl was seriously unhinged.

Whatever. Honestly – I’m just surprised that you, of all people, don’t believe me.

What's that supposed to mean?

Don’t be dumb. I saw the way you talked to them. The way your mouth moved. All of a sudden, you have this different voice, different spine. Everything different, just so you could – I don’t know. Just so you could line up with them. Like, fit against them.

Seriously – what are you talking about?

The girl reached out, grabbed Temidayo’s forearm. You literally built yourself this – contraption. I can’t imagine how many years of magic that must have taken. But you can’t even bring yourself to believe in invisibility?

Temidayo shuddered at the girl's words. They reminded him of his mother, a superstitious, spiritual woman, who used the same sorts of words when coaching Temidayo on how to fashion his body. Soyinka magic, she would say. Cast another Soyinka spell. It had been quaint when he was younger, but as he grew older he found it irritating. It made her sound old, and crazy. Temidayo found other, better ways to describe how he had come to inhabit the body he lived within now. Hard work. Grit. Education. Determination. And for the very first time since meeting this girl, his mouth moved of its own accord to talk to her.

I have no idea what you’re talking about, he said. I don’t believe in magic.

A look of something – pity? – flooded the girl’s face. She stepped closer to Temidayo, so close their chests were almost touching, and then brought her hand up, and traced her index finger lightly over Temidayo’s lips. Citrus filled his nostrils. In his ears, the cacophony of the ocean. He found himself praying that she would kiss him. But once her finger had finished navigating the circumference of his mouth, she just dropped her hand, and stepped away.

It’s beautifully designed, the girl said. But the whole time I was watching you talk to that girl, I kept thinking - whoever made that mouth must hate him. Because why would anyone want to line up with these people? And then I tapped you on the shoulder, and you couldn’t see me, you couldn’t see me because your eyes were all lined up with their eyes, and I realized, oh my god, he made that mouth! He made it all by himself. And I was surprised. And then I was annoyed. And then – well. Forget it.

The girl tilted her head then, and squinted at Temidayo, like she was trying to read words printed very faintly on his forehead. Temidayo felt a familiar tug at the bottom of his stomach. He dared to smile at her.

And then what?

Nothing.

It’s something! Say.

I was annoyed, she said. But then – honestly, I was a little impressed.

The girl rolled her eyes, and Temidayo saw them glint. And the sight of that sparkling metal was enough for Temidayo to follow her to the train station. She did not complain, and she did not complain when he sat down next to her on the train. But she didn’t say anything, either, and neither did Temidayo. He had no idea what he was supposed to say next. He knew the smart thing to do would be to leave the girl alone, go back to wordless waves in the park. But her smile, her beauty, the way Temidayo had felt when she stood near him and touched his mouth – it was all enough to make him want to stay near her.

Finally, the train arrived at their stop, and they got off together, and walked the three blocks to their building. In the lobby, Temidayo broke the silence:

Listen. I’m sorry. About Claire.

The girl snorted. Not as sorry as I am.

Um. Do you want to come up? To my place?

Her smile was the breaking open of an orange - juice sprayed everywhere. Sure, she said. Sure.

She was perfect there on his couch, her feet kicked up and curled underneath her legs. Her body, one smooth curve, the gesture of a waterfall every time breath moved through her shoulders. Temidayo poured them both wine. The girl took the glass in both hands and took a dainty sip, staring at Temidayo’s apartment.

It’s bigger than mine, she said.

Really? I want to see yours.

We’ll see about that.

Temidayo sat down next to her, close enough that he could feel the breath leaving her lips. That citrus scent. He imagined their bodies together in lush gardens, enmeshed in each other, falling apart and then coming back together, ripe and glistening. She looked at him, and he could tell she saw his imagination, and she was smiling, like she approved of Temidayo’s vision for their future.

He kissed her.

After a couple seconds, she pulled back, giggling. Temidayo frowned.

What’s so funny?

Sorry, sorry. It’s just - your mouth. Your mouth!

What about it? Temidayo asked, wearily.

It’s so strange. The girl giggled again. Why would anyone want a mouth like that?

Temidayo was annoyed. It’s literally just my mouth. I didn’t make it with magic, or whatever you think.

Oh. Don’t be like that.

Like what?

The girl looked at Temidayo with the same expression from earlier - yes, it was pity - and brushed the side of his face with her hand.

I noticed you, she said, the very first day I moved into the building. And I thought you were so interesting. Most people are just given bodies, and that’s what they stick with. They never even try to change them, at least not in inventive ways. But you – I could tell you made this whole thing all by yourself, just to live inside.

As she spoke, she traced her index finger down Temidayo’s chest. It reminded me of me, she said.

Hearing her say this filled Temidayo with something heavy, syrupy.

Should we - move to my bed?

God no. I’m not going to have sex with you.

Oh – I mean, okay. I mean, that’s fine.

Don’t feel bad about it. I mean, I sort of want to. But I only have sex with people who love me. It’s a new rule I have.

Okay, Temidayo said. They sat quietly for a moment.

Well, Temidayo said, finally. I might actually be in love with you. Not to sound crazy but - I’ve been thinking about you all winter.

And it was like Temidayo’s words had broken her heart. He had never seen a sadder face.

Have you really?

Seriously. It’s honestly embarrassing to admit. I definitely – really like you.

Sure. But – you don't love me, she said. She was looking at his lips.

Temidayo looked at hers. Maybe you could teach me?

An accounting took place behind the girl's eyes. Then, she took his head in both of her hands and drew him close. She kissed his eyelids, and then his mouth, and then the top of his head. Soft. Ginger. Careful. She held Temidayo, and he could feel himself being held, could feel her body supersuming him, taking him over. He felt calm. He wanted just to lie there, with his head underneath her chin, his body curled up under hers. As Temidayo drifted off to sleep, the girl began to hum, and the song sounded exactly like the afternoon’s ocean.

When Temidayo woke, the girl was by the door, sliding on her shoes.

Hey. Wait.

She looked at him, and smiled. I have to go. But - I did it.

Did what?

Taught you how to love me.

Oh yeah? Temidayo yawned. And how did you do that?

Well, I turned you into a tree.

Temidayo laughed.

I’m not joking.

She sounded so serious that Temidayo sat up.

Wait. You did what?

My god. Listen to what I'm saying. I turned you into a tree.

It’s just – obviously I’m not a tree. I’m a person.

The girl grinned. Give it some time.

Okay, Temidayo said, and then rubbed the back of his neck. Talking to this girl was like solving riddles. So.

So – what?

So – do you sleep with trees?

The girl began to laugh. And she kept on laughing, and laughing, and laughing. Even after she left, and closed the door behind her, Temidayo could hear her laugh echoing down the hallway.

This was the story that Temidayo told to Jack, in stutters and starts. But the story Jack heard was very different. By the end, he was laughing. You have to move to the city, he said. Girls in Brooklyn are insane.

Jack’s words bounced off Temidayo’s ears. Speaking the story out loud had let the truth of the situation settle into his bones. The body he had was no longer the one he had built. His feeling of sickness had been replaced by one, urgent need – to be on the ground. To feel dirt. He had to go to the park. He stood up, wordlessly.

Hey, Jack said. Hey! You can’t leave.

And before, Temidayo’s body would have listened. But this was a new body. He could leave. He did.

The air in the park was cooler, wetter. He walked to the girl’s favorite spot - the grove by the boathouse, between the two trees, right at the edge of the forest. He leaned his back against the bigger trunk. Temidayo could feel the water resting heavy in the membranes of the tree’s leaves. Everything rustling, moving, beating. Endless chatter - like the ocean, but a little quieter. More formed. So many living things – Temidayo had been to this park so often, and he had never paid attention to it, all of these beings wrapped up in a remarkable chorus. A churn. It was a whole other city.

The two trees he was sitting between were two uncles, he could tell now. Standing hefty, their roots knuckled into the dirt with a concrete grip. Arms splayed out in grand display of branch and leaf. They were never going anywhere. They looked down at Temidayo and laughed.

Look at this young one, the first uncle said.

This is the one she told us about, yes? The second uncle said.

Oh yes. And he doesn’t know a thing, the first uncle said.

I can year you, Temidayo said to them, dumbly. How can I hear you?

The two uncles roared with laughter, and the sound was a rustle, a gust of wind.

He’ll learn, the first uncle said.

Eventually, the second uncle said.

But for now - what a fun treat! The first uncle said. Everyone, come. Listen to this little, stupid thing.

The forest rushed forward and yawned open, expanding out over Temidayo. Everyone coming to witness him. When they saw him, they laughed with delight. Joy, in such slow motion – a leaf curling a ringlet of moonlight around its languid body, acorns swelling, bending the branches they perched on towards the ground. Temidayo could feel the pulsing water flowing within everything all at once, everyone sharing the same heartbeat, breath, song. Tremendous chorus.

And Temidayo sat there in the dark, and listened. He had never realized, before, how small his body was, how limiting. How all of his tiny alterations and changes had warped it over time, turned it into a cage with the wires facing inward, poking at him all day and all night. Now, he felt open, expansive, grand.

The sun began to rise, and Temidayo took his place between the uncles. When he looked down, he wasn’t surprised to see that his legs had disappeared, replaced by a trunk. He let his roots push into the dirt. He drank from the earth and the sun. He closed his eyes. And, for the first time in a long time, he breathed. He grew.